|

|

|

THIRD AIR CARGO UNIT

(Known to the Twenty-Seventh Troop Carrier Squadron as

Third Air Drop Unit)

![]()

The historic march of General Stilwell from Burma in early 1942 left the far corners of the country open to easy penetration by the victory glutted Japanese army. The dogged Chinese troops desperately resisting in the East were now almost wholly dependent upon the Burma Road for aid from the outside world. By virtue of their Burma victory the Japanese now had a strangle hold upon China’s life line of supply. Shortly afterwards the Imperial Army had advanced beyond the borders of Burma to Paoshan located 30 miles east of the Salween River.

In April of 1944 a major offensive of the Chinese army was launched in Southwestern Yunnan Province. This drive was coordinated with the offensive of the American and British Armies which were prodding the Japs from West and Northwest Burma. The objective of this total effort was the eventual liberation of Burma and the rupture of Japan’s grip upon China’s main artery.

The terrain in which China’s operations were to be carried on presented numerous tactical problems. Foremost among these was the difficulty of effective supply. The campaign was waged in the scraggy heights of the Kaoli Kung branch of the Himalaya mountains. The almost complete lack of adequate land routes and the mountainous features of the terrain made the supply of the front line troops by air an absolute necessity.

The task was not accomplished

merely at the conception of the plan. It remained for Headquarters

to recruit both experienced and inexperienced men and mold them into an

efficient unit. Air Supply Dropping operations had been carried on from

Dinjam and Sookerating in the West Burma Campaign, but no such unit was

existent in China to assume the responsibility for such a task. Lieutenant

Sweeney of Y-Forces was sent to Dinjan in February to familiarize himself

with the complexities of the work. On 20 April, he returned to the Y-Forces

Base at Yunnanyi, China and was followed a few days later by six First

Troop Carrier Squadron planes with experienced drop crews aboard. However,

within the week both planes and personnel were recalled to the India unit.

By the end of April four experienced packers arrived from the India unit for duty in the Yunnanyi warehouses. On 3 May Lieutenant Edward Chinn joined and was assigned as officer in charge of operations. Captain Oakley and seven veterans of the Burma Campaign reported from India on 16 May. They were joined six days later by Lieutenant Henry Wong.

An auxiliary Air Drop detachment was considered advisable and on 24 May Lieutenant Sweeney with a small complement of men was sent to Paoshan for that purpose. However, developments ensued which proved the plan unfeasible. On 4 July, the detail returned to the main unit in Yunnanyi.

Lieutenant Francis H. Sherry reported to the unit on 28 May bringing with him thirty veterans of the Dinjan and Sookerating units. On the same day the first missions were flown in planes of the 27TH Troop Carrier Squadron. The planes dropped at target Number One, located just across the Salween River to the north.

Twenty five volunteers from the Calcutta casual camp reached the unit on 31 May. They were followed da few days later by five more. On this date the strength of the organization had reached 101 including four officers and four men on detached service from Y-Force.

Major Wolfe arrived

on 5 June and on 7 June, he assumed command of the detachment. Five days

later, Lieutenant George Jeffrey reported for duty. On 18 June Sergeant

Urgitis was appointed acting first sergeant. By this time operations had

increased in temp and fourteen warehouses were now in use to supply the

immediate needs of the front line troops. On 18 July, for the administrative

convenience of higher headquarters, the air crew members were operationally

attached to the 27TH Troop Carrier Squadron. The following day all of the

volunteers from the 478Th Quartermaster Truck Company, were transferred

to Y-Force. Only the four Hospital men were still on detached service.

On 31 July, Sergeant William Bottoms was appointed first sergeant to replace

Sergeant Urgitis as acting first sergeant.

From time to time, Air Drop was called upon to serve in a special capacity. Toward the end of July the Japanese advance toward inland China bases, had reached serious proportions. The Strategically important American Air Base at Hengyang was besieged and even Kweilin was in danger of being overrun by the Japanese onslaught. Several men were sent on detached service to Kweilin to pack and drop urgently needed supplies to the defenders of Hengyang. When the ferocity of the offensive finally touched Kweilin, secret missions were dispatched by the unit to assist in preparations for the evacuation. In April of 1945, when the tactical situation in China was brighter for the Americans than in preceding year, secret missions were flown from Chengkung to supply French and American units working behind the enemy lines. One plane penetrated as far south as the Gulf of Tonkin and the crew members glimpsed their first view of the China coast. It was believed to have been the first plane, at that time, to proceed so deep into enemy territory unarmed and return.

The unit has frequently been singled out for honors by the award of medals and citations to certain of its men. On 15 September, Brigadier General Dorn of Y-Force arrived at the base for the purpose of presenting Air Medals to nine men of the detachment.

On 24 September, thirty men joined from Replacement Center Number 3. Apparently the MOS numbers of these men were rather generously assigned. Many who were supposed to be kickers had never been in a plane, and most of those classified as riggers had never had instructions in chute packing.

The campaign had now progressed to the point where land loads at Paoshan were practical. On 29 September, four loads had been landed at Paoshan to start the program. Meanwhile, the operational efficiency of the unit had increased to the point where 51 missions were completed in one day with ten planes.

On 4 October sixteen men arrived from Calcutta. On the 21st and 22nd man previously assigned to a pigeon company reported for duty. Between 7 November and 14 November, three of our grounded men were exchanged for three Motor Transport Battalion men desiring to fly.

On 16 November, the outfit was again called upon to fly special missions during the defense and evacuation of Kweilin.

On 18 November, Air

Medals were presented to twenty-two men by Colonel J. C. Kennedy of the

69TH Composite Wing. One week later, Major Bullock, post commander of Yoke

Depot No. 2, presented twenty-one more Air Medals.

Air Dropping operations were fraught with dangers, and for this reason almost without exception the flying personnel of the unit was recruited from volunteer lists. The mountainous terrain and the scarcity of passable trails often made it necessary for the ground forces to locate their target almost at the firing line. In order to drop in the area specified the planes were frequently forced to complete part of their patterns low over the Japanese lines thus exposing themselves to enemy rifle and automatic weapon fire. Anti-aircraft fire and lobbed mortar shells were encountered several occasions. The operations were carried on within convient range of enemy fighter fields and the possibility of such attack was not the least of the perils involved.

In addition to the usual hazards of war the operations were made even more difficult by weeks of bad weather. The proper maintenance of the planes was impossible for lack of equipment and the absolute necessity for every available ship on the line. In the even of engine trouble the jagged terrain offered little chance of a successful crash landing.

Considered against the background of these difficulties our casualties may be considered unusually light. On 31 May, Lieutenant Hunt, through his skill, averted a tragedy when the engines of Number 974 sputtered out on the takeoff. No one aboard sustained injured. Five days later the same plane developed engine trouble in flight to the drop target. The Air Drop crew aboard, jettisoned the load, but the effort proved futile. Lieutenant Hunt made a successful crash landing in a rice paddy near Pupeiow, China. The crew again emerged unhurt. The Air Drop personnel aboard were commended for their efficiency in the face of danger.

On 18 August, enemy air opposition disrupted operations in the sector just west of the Salween River. A Japanese “Zero” hovering in the vicinity of target Number 55, swooped down upon two Air Drop ships approaching the dropping area. The pilot of Number 930, attempted to climb into the safety of the clouds, but he was hopelessly outclassed by the “Zero.” The plane crashed in flames, but several days later the remains of the crew, with the exception of the crew chief, were found and interred at Paoshan. The Air Droppers killed in action were Pfc Kowalick, Pvt. Clark and Pvt. Lawson.

The second plane escaped

the same fate by diving at a terrific speed and leveling out low over the

Salween River bed.

On 23 September 680 failed to return from a mission. The flights operating from the field the next morning discovered the wreck in a ravine west of Mitu. Several days later a search plane verified the location of the wreck and a search party was dispatched at once. Upon arrival of the search party, they found the plane on its back, but unburned with all the personnel aboard dead. The body of Pvt. Missin, the only Air Drop personnel aboard, was found stripped of clothing some fifty yards from the wreck.

The afternoon of 10 January 1945 “AB” took off for a drop mission at the target area located near Wanting. During the operations over the target, the plane encountered heavy ground fire from nearby Japanese troops. After disposing of its load the plane headed home. A few miles west of Paosha, one of the motors, disabled from the ground fire, cut out completely. Shortly afterwards, the other motor began to smoke badly. The pilot made an unsuccessful attempt to crash land on the runway, but an echelon of fighters on the line prevented his doing so. The plane was crash landed in a rice paddy near the field and was damaged beyond repair. All members of the crew were hospitalized. Sgt. Sherman and Cpl Baker stained only minor injuries, but Cpl. Wolfenbargar received painful and serious injuries to his left knee cap.

By the summer of 1944, the constant exposure to common dangers and hardships had closely knited the unit together. A certain esprit de corps had developed, but morale was not as high as might be desired. So far as it was within the province of the unit officers to do so the needs of the men satisfied. The chief causes of complaint came from sources beyond the control of the unit.

The overworked men

were tired both mentally and physically. Many of them were billeted in

a dismal, rat infested barrack. The food was often so poor as to be inedible.

But most sensitive of all their hurts was the complete absence of any tangible

reward from higher headquarters for the services they had given. Rating

lists were repeatedly submitted for the men, but each time they were returned

disapproved. For months the unit had played a major role in the campaign

and yet it hadn’t been accorded the dignity and the attendant benefits

of activation. Only the hope of eventual absorption into the Air Force

kept its efficiency at a high level.

Buoyant rumors had been penetrating the general gloom to the effect that activation into the Air Force was forthcoming. On 15 June there was cause for rejoicing in the Air Drop Detachment. A radiogram had been received from Rear Echelon by Major Wolfe advising him that the detachment was to be activated as an Air Force Unit and designated as 3RD Air Cargo Resupply Detachment. The future strength of the unit was set at 142 including 6 officers. It was specified that they were to function as six teams.

The official proceedings which were to actually bring the dream to reality became complicated by administrative difficulties in higher headquarters. The disheartening news soon came that plans for the proposed activation of the China Air Drop Unit had been suspended in favor of the detachment serving with 2ND Troop Carrier Squadron in Burma. The unit morale had soared to new heights but upon receipt of this news it had lost its motivating force and just as quickly plummeted to even lower depths than before.

On 23 December, appropriately arriving during the ‘Season of Good Cheer,’ a second radiogram was received notifying Major Wolfe that the unit was to be activated and transferred to the theater Command pursuant to the provisions of Column 8 and 16 of T.O./E 1-460 dated 23 May 1944. The organization was to be designated as 3RD Air Cargo Resupply Detachment and was to have a strength; of 85 enlisted men and 4 officers.

On 8 January 1945 China Theater Headquarters transferred the unit to the Fourteenth Air Force and assigned it to duty with C.A.S.C. Lieutenant Edward Chinn was promoted to the grade of Captain and was appointed Commanding Officer of the organization.

By December, the persistent efforts of the Chinese had pushed the Japanese beyond the Mangshih airstrip and the fall of Wanting was now imminent. With Wanting in Chinese hands the major objective of the campaign would be accomplished. The long locked back door to China would be reopened and the campaign would come to a successful close.

The Air Drop Detachment

anticipating the end of the campaign began to move its warehouse facilities

and personnel to Chanyi from where it could operate in the forth coming

Eastern campaign. On 5 December Major Wolfe reported to the Base Commander

at Chanyi and outlined the mess requirements and billeting needs of the

men to follow. On the following day work began on the leveling of the camp

site. The selection of an operational area was made and one warehouse

and a shed were assigned to the outfit for its use. On the same day,

Lieutenant Henry Wong arrived with 18 enlisted men and 2 interpreters.

By 7 December, arrangements had been completed for the services of necessary Chinese labor. Tradition was shattered when a clause was introduced by Major Wolfe providing that the workers per paid directly thus eliminating the ‘honorable squeeze.’ Guards for all operational facilities were arranged for. By nightfall four tents had been erected in the area. On the morning of 11 December, ammunition began to arrive at the rail head at the rate of 50 tons a day to be accommodated by our trucking and warehouse facilities. Shortly afterwards, men and supplies began to arrive daily from Yunnanyi.

Only 20 fliers were left at Yunnanyi to handle the few drop loads that were still called for. Unfortunately, early in January, Wanting fell to a Japanese counterattack which proved that the move to Chanyi, had been somewhat premature. The small complement of men left behind flew from dawn until after midnight without respite. It was some time before relief arrived from Chanyi. Finally, late in January, Wanting was retaken and held by the Chinese. On 1 February, the men stationed at Yunnanyi had the complete satisfaction of seeing their months of effort rewarded by the appearance of the first truck convoy to arrive from India since early 1942.

By the middle of February, almost the total strength of the unit was located at Chanyi. Several men were left behind to handle warehouse details at Yunnanyi. Two men were sent to Kunming to expedite our truck traffic through there. It was by now apparent that operations from Chanyi would not begin in the immediate future.

At the suggestion of Lieutenant Henry Wong, work was begun on a day room and club. After two months of sporadic work the club was completed. The results of their efforts were far beyond the expectations of any of the men.

This project had served

to alleviate the monotony of operational inactivity. Furthermore, the individual

interests and cliques spawned from the necessity of billeting the men in

tents have been dissolved to a great extend. The efforts of these

separate entities are now directed to the common good of the unit. One

of the chief benefits the club had offered had been the frequent but formal

associations between officers and enlisted personnel of the detachment.

In the middle of March, thirty men were sent to Chengkung on detached service. The 27TH Troop Carrier Squadron was active there and it was believed that the men would have opportunity to save their flight pay. The attempt proved abortive and the men returned with the exception of a few warehouse workers late in April. Because of the crisis at Chickiang it was necessary to load all planes to capacity. For this reason many of the men returned without having flown at all.

The organization prospered generally from its transfer to the 14TH Air Force. The men appreciated the self respect which activation brought to the unit. Ratings were distributed with reasonable regularity. Morale had improved considerably.

However, the unit had served in a tactical capacity with the 69TH Wing through the Salween Campaign. In the light of this its recent assignment to a Service Group seemed strange. Service headquarters could not be expected to be cognizant of the peculiar needs of a combat unit. Rotation was almost impossible regardless of the fact that many of the men had served 26 months overseas and had completed hundreds of combat hours. Proper flying equipment and various incidental necessities were more difficult to obtain through these channels. Captain Chinn and the unit headquarters recognized the difficulties of operating through such channels and made repeated requests for transfer of the unit to tactical headquarters.

Finally on 1 April, through the generous efforts of Brigadier General J. C. Kennedy, 3RD Air Cargo was taken into the 69TH Composite Wing. It would be more accurately termed as being taken “under the Wing” for shortly thereafter the benefits of such an arrangement became apparent. In early 22 April twenty two men of the detachment received their orders to return to the States. On 1 May, orders came through releasing three more men for furlough in the States. The last came unexpectedly in as much as the men had not completed two years of foreign service. For the first time in its history the Air Drop Detachment had tangible evidence that an ‘hour ruling” was in existence.

At the end of April, Brigadier General J. C. Kennedy honored the organization by a visit for the purpose of presenting awards. Thirty-five men received DFC’s thirty-seven men received Air Medals, eight the Oak Leaf Cluster and four Bronze Stars were present by the General. Captain Edward Chinn was one of the recipients of the Bronze Star Medal.

![]()

K. J. FLYNN

2ND Lt., FA.,

Unit Historical Officer

CERTIFIED OFFICIAL:

EDWARD CHINN

Captain, Air Corps,

Commanding

Brig. Gen. Frank Dorn, Commander of Y Forces, is shown

awarding the Distinguished Flying Cross to William J. Bottoms of Third

Air Cargo Unit. (Yunnanyi, Yunnan, China, September 1944.

Shortly thereafter Bottoms was promoted to First Sergeant

of the Third.

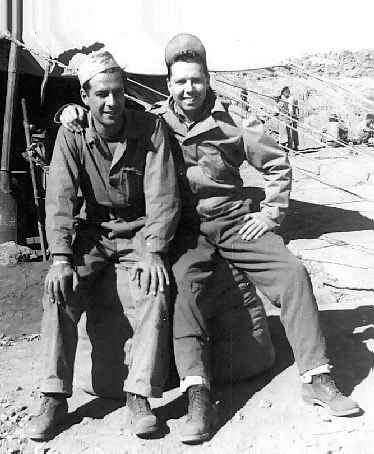

Sgt. Fred Miller of Third Air Cargo (on the left) with S/Sgt. Jack Claflin of the Twenty-Seventh Troop Carrier Squadron, Yunnanyi, Yunan, China - 1944

Although unofficial, this insignia was conceived in China at the time the unit was flying combat missions with the Twenty Seventh Troop Carrier Squadron. It was used through the balance of the war and in the post war era.

USAF Historical Research

Center

Maxwell Field, Alabama

thru

Harry A. Blair

Historian

Twenty-Seventh Troop

Carrier Squadron

La Crosse, Wisconsin

2 February 2000